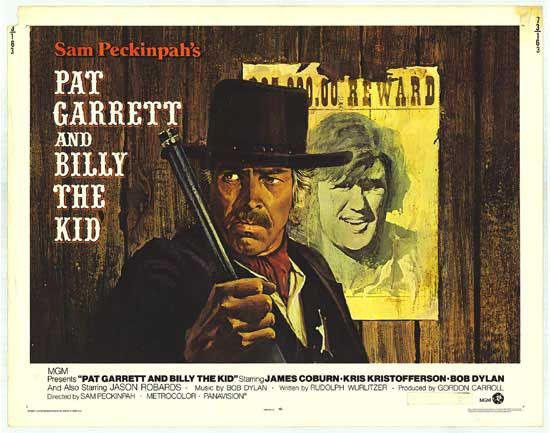

Myrtle Vail (left) as Myrt and Donna Damerel (right) as Marge.

Myrtle Vail (left) as Myrt and Donna Damerel (right) as Marge.“

Myrt and Marge” began as a popular radio show sponsored by Wrigley’s chewing gum (with the leading character’s last names being that of their popular products: Spear and Minter); the series later featured STRANGER ON A TRAIN’s favorite psychopath Robert Walker between the years of 1940-42.

The story in the film, as from what I know about the radio show, concerns a failing vaudeville troupe, and the new blood (represented by Marge, first introduced here to

Myrt, making it an "origins" tale) hired to shake and whip things up into a success once again. This is where the

similarities between the two end, as Ted

Healy and his Three Stooges show up as knockabout,

knuckleheaded stagehands, and Ray Hedges essays the role of costume handler Clarence, an effeminate who needs to be told not to try on the women’s clothes (“Selfish!” he playfully intones to the girls).

Regrettably, this innocuous programmer that’s barely over an hour and marks

Myrt and Marge's only feature film, is not as frenetic/free-wheeling, or as funny for that matter, as LOOK WHO’S LAUGHING and HERE WE GO AGAIN, Allan

Dwan’s two radio-to-film adaptations of the Fibber McGee & Molly show (with both films featuring memorable turns by ventriloquist Charlie McCarthy). Here, the most

conspicuous problem may be the incongruously contrasting tones that rub up against one another: namely, the unfortunate lapses into heart-tugging territory (the attendant feelings that come with growing older, with

Myrt realizing that she’s the reason the troupe’s not doing as well as before) that are followed in short proximity by routine eye-gauging courtesy of Moe, Larry and Curly.

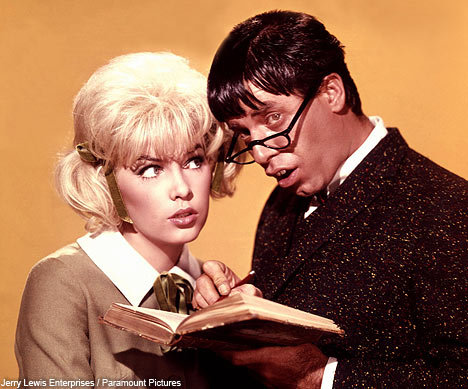

The most curious factoid here – indeed, why I watched the film in the first place - is Myrt and Marge’s relation to cult cinema royalty: Myrt being Myrtle Vail, grandmother of Charles B. Griffith, Roger Corman’s treasured scriptwriter back in the day, and Donna Damerel (Marge) being Griffith’s mother (tragically, she passed away after giving birth to her third child in 1941). Myrtle later turned up in the Griffith-scripted A BUCKET OF BLOOD and occupied a sizable role (and unforgettable performance) as the pill-popping nuisance of a mother to Seymour Krelboyne in the THE LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS. Always actively involved in her grandson’s contributions to low-budget exploitation filmmaking, she even mailed the script for CREATURE OF THE HAUNTED SEA to Puerto Rico when Corman requested Griffith do another reworking of NAKED PARADISE (Corman, 1957). Myrtle passed away in 1978 at the age of 90.

I’ve never heard of co-writer/director Boasberg, but even though his direction isn’t particularly remarkable, it’s interesting to find out that he began as a writer for Buster Keaton and others, and continued to work in this capacity even when he moved into directing, something not entirely widespread during this period in Hollywood.

----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- -----

More information on director Al Boasberg, from a subsection of the Library of Congress’ website that deals exclusively with vaudeville and variety show comedy (the link also contains copies of actual telegrams of gags written by Boasberg and sent to Bob Hope!):

“Al Boasberg (1892--1937) was one of the most prolific comedy writers for variety acts. He wrote for vaudeville, nightclub appearances, motion pictures, and radio. At one time Al Boasberg was said to be receiving royalties from 150 different acts. Boasberg wrote for Bob Hope's acts in 1930 and 1931. Among his other clients were Block and Sully, the Marx Brothers, Sophie Tucker, Eddie Cantor, Jack Benny and Burns and Allen. Boasberg was responsible for the treasured Burns and Allen routine, "Lamb Chops," and the stateroom scene in the Marx Brothers' A Night at the Opera. At the time of Boasberg's death, Jack Benny called him "America's greatest natural gagman.”

Labels: Al Boasberg, Bob Hope, Charles B. Griffith, Myrt and Marge

My LP Collection

My LP Collection