The inaugural entry in Amicus Productions’ not quite ten year run of pleasantly engaging, visually arresting, and oft-imitated brand of devious anthology horror (counting the other Max Rosenberg and Milton Subotsky co-production TALES THAT WITNESS MADNESS, but discounting 1980’s THE MONSTER CLUB, solely produced by one-half of Amicus -- Subotsky -- but still appearing under the banner anyway), DR. TERROR’S HOUSE OF HORRORS remains the colourful yardstick by which these later releases (TORTURE GARDEN, 1967; THE HOUSE THAT DRIPPED BLOOD, 1970; ASYLUM, 1972; TALES FROM THE CRYPT, 1972; VAULT OF HORROR, 1973; FROM BEYOND THE GRAVE, 1973; and TALES THAT WITNESS MADNESS, 1974) are commonly measured against. And with the notable exception of the EC Comics-derived TALES FROM THE CRYPT (also directed by Freddie Francis), none would prove to be as satisfactorily stunning as this original rendering of placing five randomly plucked strangers in closed quarters before a menacing entity, who gradually speaks of the inevitable, horrid fates awaiting our (sometimes morally compromised) protagonists, told in flash-forward (or should that be flash

back?) form.

Should our unlucky five ever arrive at their intended destinations (DR. TERROR’S HOUSE OF HORRORS) -- or escape the immaculately lily-white room and malfunctioning elevator (VAULT OF HORROR), or make it out of the remote dank cave located somewhere in England (TALES FROM THE CRYPT) -- the ghastly destinies generously elaborated on by our Cryptkeeper (Ralph Richardson in CRYPT) -- or impish Dr. Diabolo (Burgess Meredith in TORTURE GARDEN), or sinister Dr. Sandor Schreck (Peter Cushing in HOUSE OF HORRORS) -- surely will come to pass, wreaking havoc on the initially skeptical upper middle class characters represented by the various rosters of international stars. But of course, that last minute twist of the knife in each film reveals that any possible evasion of these unpleasant futures is but a charade – the envelopes containing their fates have already been sealed and preconceived, everyone’s on their pathway to eternal damnation, and the past ninety minutes have been but a mere detour on the way to the fiery pits of hell.

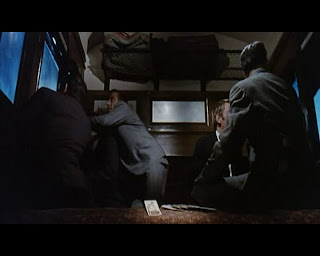

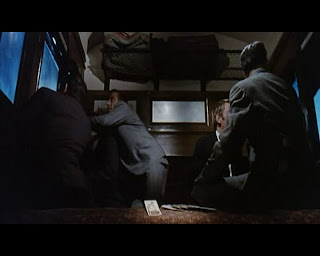

The wraparound is as simplistic and unassuming as it gets. Five commuters board a rickety train cabin (obviously a set) and await their respective long journeys ahead. Architect Jim Dawson (Neil McCallum) is heading for the west coast of Scotland, to the cozy estate where he once grew up, while jazz trumpeter Biff Bailey (Roy Castle) is making his way to the West Indies for a paid gig; on their way back to England, for either business or family, are Bill Rogers (UK disc jockey Alan Freeman), snobbish art critic Franklyn Marsh (Christopher Lee) and devoted husband Bob Carroll (a baby-faced Donald Sutherland). A sixth gentleman with feral facial hair joins the party at the last minute, a man who will only later introduce himself as Sandor Schreck (a can’t-take-your-eyes-off-of-him Peter Cushing). A clumsy move on the behalf of Schreck (but upon reflection, obviously predetermined in light of the revelation of his dark secret identity) results in the spilling of a deck of tarot cards; curiously amused, all five allow (with the fussy Lee being the most determined not to) Schreck to shuffle and deal, and thus begins the telling of their futures as it’s foretold by the seemingly random display of cards.

The wraparound is as simplistic and unassuming as it gets. Five commuters board a rickety train cabin (obviously a set) and await their respective long journeys ahead. Architect Jim Dawson (Neil McCallum) is heading for the west coast of Scotland, to the cozy estate where he once grew up, while jazz trumpeter Biff Bailey (Roy Castle) is making his way to the West Indies for a paid gig; on their way back to England, for either business or family, are Bill Rogers (UK disc jockey Alan Freeman), snobbish art critic Franklyn Marsh (Christopher Lee) and devoted husband Bob Carroll (a baby-faced Donald Sutherland). A sixth gentleman with feral facial hair joins the party at the last minute, a man who will only later introduce himself as Sandor Schreck (a can’t-take-your-eyes-off-of-him Peter Cushing). A clumsy move on the behalf of Schreck (but upon reflection, obviously predetermined in light of the revelation of his dark secret identity) results in the spilling of a deck of tarot cards; curiously amused, all five allow (with the fussy Lee being the most determined not to) Schreck to shuffle and deal, and thus begins the telling of their futures as it’s foretold by the seemingly random display of cards.

The cramped compartment here really allows director Freddie Francis to include all six central cast members in just about every shot, and it’s this stuffy atmosphere that permeates and gestates in these linking segments, a claustrophobia that only gains in intensity on the faces of the doomed protagonists as they learn the gruesome details of just how they’re damned (and in addition, the corollary of exactly why they’re here), with the added benefit of seeing a devilishly reserved Cushing registering and silently delighting in their troubles.

“Werewolf” kicks things off with the aforementioned Jim Dawson (McCallum) arriving at the residence where he was raised. A family has since moved in, but they’re accommodating his stay, as he’s there to ply his trade and knock down a wall in order to open up the living room. After a series of mysterious murders, Dawson discovers a coffin in the basement and immediately suspects a werewolf, enough so to melt down an ancestral heirloom (a silver cross) into bullets. Setting up shop in this cobweb-infested crypt, Dawson awaits nightfall, only to have his attention placed elsewhere as the ethereal presence emerges once again into the night. Racing up the stairs, he’s accosted by the new matriarch who brings Dawson up to speed on the resurrection and familiar curse that has now been lifted, thanks to his entrance into the dwelling.

“Werewolf” kicks things off with the aforementioned Jim Dawson (McCallum) arriving at the residence where he was raised. A family has since moved in, but they’re accommodating his stay, as he’s there to ply his trade and knock down a wall in order to open up the living room. After a series of mysterious murders, Dawson discovers a coffin in the basement and immediately suspects a werewolf, enough so to melt down an ancestral heirloom (a silver cross) into bullets. Setting up shop in this cobweb-infested crypt, Dawson awaits nightfall, only to have his attention placed elsewhere as the ethereal presence emerges once again into the night. Racing up the stairs, he’s accosted by the new matriarch who brings Dawson up to speed on the resurrection and familiar curse that has now been lifted, thanks to his entrance into the dwelling.

Despite some early foggy exteriors that could be classified as clichéd and in the tradition of gothic horrors, Francis keeps the proceedings realistic up to a point, with the otherworldly aspects played close to his chest before letting loose alongside the malicious intent of the matriarch – as she begins her spiel, Francis delivers bright splashes of greens and oranges that serve as highlights on the elderly actress’ mesmerizing pair of eyes.

As we will see, Francis keeps this stylistic pattern of sedate and serene compositions, followed by a swirling and vibrant array of multicolored gels to signify oncoming threats, throughout the film, with the exclusion of the second story, “Creeping Vine”, which is set during daytime and thus bright and sunny. And this works as a thematic context also, as Freeman does battle with this indestructible vegetation (with the help of Bernard Lee, or “M” from the James Bond series), daylight should be a dreadfully frightful factor as it provides nutrition and growth for this strangling shrubbery (but like most second momentum-killing anthology episodes, there’s a devoid of shocks, making for the weakest tale in a group that’s otherwise resolutely strong).

As we will see, Francis keeps this stylistic pattern of sedate and serene compositions, followed by a swirling and vibrant array of multicolored gels to signify oncoming threats, throughout the film, with the exclusion of the second story, “Creeping Vine”, which is set during daytime and thus bright and sunny. And this works as a thematic context also, as Freeman does battle with this indestructible vegetation (with the help of Bernard Lee, or “M” from the James Bond series), daylight should be a dreadfully frightful factor as it provides nutrition and growth for this strangling shrubbery (but like most second momentum-killing anthology episodes, there’s a devoid of shocks, making for the weakest tale in a group that’s otherwise resolutely strong).

It could be said that “Voodoo” is producer and screenwriter Milton Subotsky’s attempt at broad humour, akin to the “Golfing Story” segment of the treasured model of anthology horror, DEAD OF NIGHT (Alberto Cavalcanti, Charles Crichton, Basil Dearden, Robert Hamer, 1945), but I think the breezy attitude can be attributed to its choice of lead actor, the real life jazz musician Roy Castle. Castle’s jovial devil-may-care delivery is the very definition of a carefree non-actor having a great deal of fun in a light dramatic role; his nature lends itself well to its tale of an avaricious jazz trumpeter meddling around with voodoo (and a demon named Dambala) in the West Indies, adopting some catchy riffs and adding them to his repertoire – to his eventual detriment.

It could be said that “Voodoo” is producer and screenwriter Milton Subotsky’s attempt at broad humour, akin to the “Golfing Story” segment of the treasured model of anthology horror, DEAD OF NIGHT (Alberto Cavalcanti, Charles Crichton, Basil Dearden, Robert Hamer, 1945), but I think the breezy attitude can be attributed to its choice of lead actor, the real life jazz musician Roy Castle. Castle’s jovial devil-may-care delivery is the very definition of a carefree non-actor having a great deal of fun in a light dramatic role; his nature lends itself well to its tale of an avaricious jazz trumpeter meddling around with voodoo (and a demon named Dambala) in the West Indies, adopting some catchy riffs and adding them to his repertoire – to his eventual detriment.

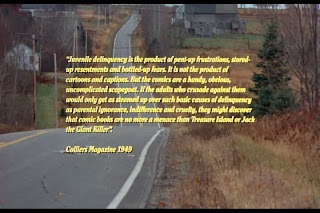

I’m convinced that the startling widescreen composition and accompanying clever obfuscation of a letter in a nearby prop (see above) is not an accident, and shows the sense of humour that Francis must have in his directorial undertakings. Other than an amusing lead performance, “Voodoo” is but a palate cleanser, gearing the spectator up for two much more memorable tales (not to mention it’s guilty of being a slightly derivative riff itself -- just witness the “Thriller” Season One episode “Papa Benjamin” from 1961, starring John Ireland and directed by Ted Post, and based on the short story by Cornell Woolrich).

“Disembodied Hand” pits two Hammer regulars at odds with one another: the shrewd art critic (Christopher Lee) vs. the sensitive, but amused artist (a cheery Michael Gough). Within this clever battle of wits is an absolute horror story that’ll make anyone who has ever made a living passing critical judgments cringe, for on a primordial level, broken down, it’s the essential tool of the artist (Gough’s chopped-up hand) that becomes fixated on destroying the eyesight of his plucky detractor (Lee’s prized eyeballs). It remains a menacing episode, probably one of my absolute favourites from any of the Amicus entries, and it gets by without a lot of the expository fat that becomes important, yet needless, in telling such succinct stories. Lee’s swift statements about the artwork of (what he doesn’t yet know to be) a chimpanzee are but one of the many witty diversions it effortlessly includes in addition to the central revenge.

“Disembodied Hand” pits two Hammer regulars at odds with one another: the shrewd art critic (Christopher Lee) vs. the sensitive, but amused artist (a cheery Michael Gough). Within this clever battle of wits is an absolute horror story that’ll make anyone who has ever made a living passing critical judgments cringe, for on a primordial level, broken down, it’s the essential tool of the artist (Gough’s chopped-up hand) that becomes fixated on destroying the eyesight of his plucky detractor (Lee’s prized eyeballs). It remains a menacing episode, probably one of my absolute favourites from any of the Amicus entries, and it gets by without a lot of the expository fat that becomes important, yet needless, in telling such succinct stories. Lee’s swift statements about the artwork of (what he doesn’t yet know to be) a chimpanzee are but one of the many witty diversions it effortlessly includes in addition to the central revenge.

The definitively titled “Vampire” is an early showcase for Donald Sutherland, who portrays a fresh-faced doctor in a new town with a bloodsucker for a wife (his first tip-off? He cuts his finger and she lovingly, even maternally, licks the wound). Supporting his unconventional belief is the resident medical practitioner who, despite his scuffle with a vampire bat, has a peculiar ulterior motive for doing so. The denouement is but a cruel, macabre punch line to an otherwise pithy segment, reminiscent of some of those last-minute “episodes” of “Night Gallery” (I’m thinking of Victor Buono’s brief pun-happy jaunt in “A Midnight Visit to the Neighborhood Blood Bank”).

The definitively titled “Vampire” is an early showcase for Donald Sutherland, who portrays a fresh-faced doctor in a new town with a bloodsucker for a wife (his first tip-off? He cuts his finger and she lovingly, even maternally, licks the wound). Supporting his unconventional belief is the resident medical practitioner who, despite his scuffle with a vampire bat, has a peculiar ulterior motive for doing so. The denouement is but a cruel, macabre punch line to an otherwise pithy segment, reminiscent of some of those last-minute “episodes” of “Night Gallery” (I’m thinking of Victor Buono’s brief pun-happy jaunt in “A Midnight Visit to the Neighborhood Blood Bank”).

Some reports have stated that Francis (who passed away only this year) seemed a bit apprehensive about and dismissive of his directorial outings, foregoing his significant forays in genre filmmaking for his work as a camera operator (THE TALES OF HOFFMANN) and cinematographer (THE INNOCENTS, THE ELEPHANT MAN, GLORY), and it’s probably for this that his peer, Terence Fisher (who once penned an article entitled “Horror is my Business”, as laconically embracing as John Ford’s “I Make Westerns” line), will forever be more endearing in the hearts of genre enthusiasts everywhere. Still, it’s us spectators in the dark that’ll have the final say, and it’s for this reason that I can’t help but reflect on Cushing’s closing bit of dialogue as Sandor Schreck whenever I’m watching an old-school British horror effort of the period and I’m not sure who signed the picture; for more often than not, the vivacious widescreen compositions seem to be shouting out that immortal question (which is used to confirm Cushing’s role as the specter of death), signaling the inimitable hand of Freddie Francis - “Have You Not Guessed?”

Some reports have stated that Francis (who passed away only this year) seemed a bit apprehensive about and dismissive of his directorial outings, foregoing his significant forays in genre filmmaking for his work as a camera operator (THE TALES OF HOFFMANN) and cinematographer (THE INNOCENTS, THE ELEPHANT MAN, GLORY), and it’s probably for this that his peer, Terence Fisher (who once penned an article entitled “Horror is my Business”, as laconically embracing as John Ford’s “I Make Westerns” line), will forever be more endearing in the hearts of genre enthusiasts everywhere. Still, it’s us spectators in the dark that’ll have the final say, and it’s for this reason that I can’t help but reflect on Cushing’s closing bit of dialogue as Sandor Schreck whenever I’m watching an old-school British horror effort of the period and I’m not sure who signed the picture; for more often than not, the vivacious widescreen compositions seem to be shouting out that immortal question (which is used to confirm Cushing’s role as the specter of death), signaling the inimitable hand of Freddie Francis - “Have You Not Guessed?”

=====================================================

=====================================================

DR. TERROR'S HOUSE OF HORRORS related media:

Edgar Wright’s commentary can be turned on/off over the trailer, housed at “Trailers from Hell”:

Labels: Amicus Productions, Christopher Lee, Dr. Terror's House of Horrors, Freddie Francis, Peter Cushing

My LP Collection

My LP Collection